Arash Hanaei: “I often think of the artist as a figure caught in a mental landscape, circling around unresolved questions rather than advancing.”

Mahsan: What initially drew you to study photography, and how did your interest in war archives during your studies come into play in your artistic direction?

Arash: I was really into painting, and it still influences me, but over time I found the process too repetitive. Photography, on the other hand, was about detailing, refining, or even manipulating reality. It felt more like a biopsy of the environment. That shift aligned more closely with how I wanted to explore my subjects. Later on, I progressively shifted toward intermedial speculations and post-internet strategies, probably a natural transition due to my background in photography.

My interest in war archives began somewhat unexpectedly. While reflecting on when it started, I remembered reading a translated excerpt from Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others in an Iranian photography magazine a long time ago. In that text, Sontag discusses early 20th-century photographs of lingchi, or “death by a thousand cuts,” emphasizing the real suffering behind them: the images left a deep impression on me. Knowing some war photographers personally, I began looking more closely at taboo images especially from the Iran-Iraq war. But I quickly moved beyond the moral framework Sontag had laid out. Faced with photographs of dismembered bodies, bones, and skulls, I entered a space of visual violence that couldn’t be reduced to ethics. Believe me! Once you’re there, there’s no going back.

Recently, while revisiting that memory for this interview, I looked for Sontag’s passage again. In the process, I accidentally came across Louis Kaplan’s essay, Unknowing Susan Sontag’s ‘Regarding’: Recutting with Georges Bataille (Postmodern Culture). Kaplan offers a sharp critique of Sontag’s interpretation of the lingchi photographs, arguing she overlooks Georges Bataille’s notion of “anguished gaiety” that strange mixture of joy and pain in the face of death: “gay anguish, anguished gaiety… where it is my joy that finally tears me apart” as quoted by Kaplan. He suggests Sontag reduces Bataille’s ideas into a moralized, even Christian, framework that ignores his atheological and transgressive thinking (Kaplan). For me, that helped clarify the difference between her framing and the far more ambiguous, metaphysical space I had entered when exploring these images.

Kaplan also draws a parallel with Jeff Wall’s Dead Troops Talk, a staged image of dead soldiers laughing and conversing. Wall himself said, “It had nothing to do with the Afghan war… but the subjects needed to be soldiers… That would surely give them something to talk about” as quoted in the Art Institute of Chicago. Kaplan notes that Sontag’s approach can’t quite account for this kind of ambiguity where horror, absurdity, and hyperrealism meet. For me, this visual uncertainty feels closer to what violence actually is: not just ethically troubling, but something that collapses meaning altogether. That’s the space I found myself drawn into not explanation, but confrontation.

Mahsan: Since you brought up Bataille, this also reminded me of his essay The Cruel Practice of Art, where he suggests that art doesn’t moralize horror but transforms it into something strangely captivating, where beauty and violence don’t cancel each other out but coexist in an uneasy tension. That idea isn’t far from what you said earlier about confronting visual violence without trying to explain it away.

I’m thinking here of your series The Benefits of Vegetarianism, where you burnt and maimed dolls. Was that act a way of enacting the cruelty you were seeing in images? Or was it more about giving form to something that can’t be represented directly?

Arash: The Benefits of Vegetarianism series emerged from a formative moment in my youth, when I came across a book of war photography. Among the most disturbing images were the victims of chemical bomb attacks bodies burned, scarred, dismembered. These weren’t just historical records, they confronted me with a kind of visual violence that went beyond representation. I didn’t yet have the language for it, but the rupture it created stayed with me. Later, I would come to understand that meaning might begin or fail to unravel in that kind of process. So, it wasn’t about witnessing suffering for ethical contemplation. It was about confronting something that couldn’t be resolved through explanation.

The dolls I staged though not the title unfortunately, were not metaphors as one critic said, they were carriers of something I had seen, internalized, and needed to pull into another visual register something staged, but still painfully real. That instinct to confront what I couldn’t express may be rooted even deeper in my childhood and the environments I moved through. I was born into an ordinary middle-class family, educated, politically quiet, what we used to call the “grey zone.” Like many families of that era, they chose silence and survival. I’m not blaming them; that was simply the logic of the large part of society. In fact, I’m grateful to have experienced it in childhood. It taught me early on that you didn’t need to be a genius to understand the situation. You just chose your path and stuck with those like yourself. Many of whom, like my father first and then my mom, chose to leave and live somewhere for a while.

Some of these immigrants never came back and died in diaspora quietly, without dreams of becoming heroes or even seeing one. We (mom, me and brother) moved to the UK, where my father was studying, and ended up in Bradford in the late 1980s, close to the end of the war. As far as I remember, Bradford was still holding onto punk and post-punk culture. I wasn’t deeply into punk music as an eight- or nine-year-old, but you couldn’t escape the atmosphere. Punk was still in the air in the aesthetics, in the streets. That was also when I started feeling more separate from my family, who were often caught up in their own conflicts. I began spending more time outside, learning to be alone, sometimes roaming the city with friends after school. That environment shaped how I would later approach form, power, and the dynamics of rupture and fragmentation in my work.

Mahsan: Many artists from your generation in Iran seemed to carry a kind of responsibility or perhaps pressure to convey a clear message about the war, politics, or to adopt a visible stance. But even as your work engages with those same histories and images, it doesn’t feel like it’s trying to speak for something or someone. It remains personal, fragmentary, often unsettling—more like an exposure than a statement. A parallel can be drawn to Deleuze’s idea in The Logic of Sensation where art isn’t about representation, but about forcing sensation into visibility, something irreducible and affective, not communicative. Your approach seems to resist resolution or alignment, even when dealing with violence or trauma.

Do you see your path as an artist as something you chose, or more as a response to personal, historical, or aesthetic forces you couldn’t ignore? And when your work avoids cliché or collective narratives, is that a deliberate choice, or simply what feels most honest to you?

Arash: I felt the pressure, but for me, it was less about the war itself and more about politics in general. Representations of the war were largely shaped by state-backed narratives, focused on propaganda, martyrdom, and heroism, and institutionalized through cinema, photography, murals, and painting. Independent reflection on the war was rare. Artists who tried were often monitored, while the broader visual art scene tended to avoid the subject, seeing it as already appropriated by the state. It was no longer neutral ground. In any case, the government prioritized cinema and music, likely because visual art had a more limited audience. But in the cultural sphere, when it came to politics, the pressure was stronger and came from both sides: from the government, as the central authority with institutional power, and from the opposition. While the opposition didn’t have the same centralized control, it still shaped a major part of the cultural discourse, especially through contemporary art, which often merged political critique with artistic practice. For many of us, that space felt closer, more open, but still carried its own expectations. In a country where political conflict permeates every level of society, even cultural expression risks being reduced to a political stance. If you don’t align clearly, you’re easily labeled apolitical, commercial, or irrelevant.

This is a logic far removed from how thinkers like Deleuze as you said and Bataille approached art. So you can imagine how difficult it is to hold a vision like that and live in a society like this. Artists like me are not building systems. We are staging their breakdown. And that breakdown is never entirely dramatic; it swings between mental dramatization and something silent, technical, and constructed. In my practice, there is no central axis. Everything is fragmented and formless, but the fragmentation is deliberate and structured. It is not chaos; it is an unfinished memory. I started building these “stages” in a more individual sense, to work on for example what happens when fear and other ungraspable reactions surface in a state of emergency, not to promote social courage!

Both Bataille and Deleuze reject the idea that art should simply communicate clear messages, but in very different ways. Deleuze sees art as a force that brings sensation to the surface, bypassing meaning and triggering something physical and immediate. Bataille goes further: he doesn’t just bypass meaning, he aims to dissolve it. His work invites rupture, excess, and what he calls “non-knowledge,” experiences that overwhelm and resist interpretation. As an artist, I work through instinct, pressure, and form. Later, I look to see who might have described something close to what I am doing. In that sense, philosophy becomes part of the work’s structure, not its origin.

Foggy Memo (2023), one of my video installations, reflects that. The structure is essential: a large open metal scaffold holds multiple layers, including a main screen showing cinematic fragments of hospital interiors, smaller elements like an industrial speaker, fluorescent lights, an architectural print, and a rotating holographic device. The space feels like a backstage area or a storage unit for forgotten scenography. It is bare, technical, even cold, but the coldness amplifies its effect. The viewer steps into a fragmented space where images don’t simply appear; they loop, stall, and delay. They create a rhythm of tension and disorientation. The sound, created in collaboration with an electro-musician, spreads through the structure like a nervous system, adding a sense of suspended emotion-anger, maybe, but also freedom, like the energy in a strike. The motorized bed visible inside the CT scan’s circular tunnel resembles both a throne and a torture device. One of the most unsettling shots shows a room the viewer never fully enters: a delivery room. At its center, a worn gynecological table with metal stirrups stands alone. These tools, meant for care, take on an ambiguous presence. They evoke clinical function, yes, but also fetishism, exposure, and surveillance. For me, that room is not just medical. It is political. It recalls both birth and torture, control and vulnerability, rendered in metal, silence, and light.

Arash Hanaei, Foggy Memo, Installation View, Revenir du Présent,Collection Lambert, 2023. Photo: David Giancatarina

Mahsan: So we’re kind of immersed in your thinking process: the structured fragmentation, the suspended resolution, the way you follow instinct rather than a fixed idea. It makes me think again of Deleuze and his idea of the Time-Image in Cinema 2, where time isn’t linear or action-driven but unfolds in layers, through hesitation, memory, and moments of waiting. He talks about how form can emerge not from coherence, but from suspension and duration. It’s not that your work is cinematic, but it shares that sense of a mental landscape unfolding, where meaning isn’t declared but slowly revealed or even withheld.

It’s also interesting how you described your approach to philosophy, not as a starting point, but as something that comes in later. I think of it as a kind of “reverse approach,” where your work grows out of your own perception and lived experience, and only afterward do you find thinkers whose ideas reflect what you’ve already created. It’s not about name-dropping to make the conversation sound intellectual; it’s about recognizing real connections that emerge through the work.

In that sense, even though Suburban Hauntology is rooted in your engagement with Jean Renaudie’s architecture, Mark Fisher also seems to come through in parts of it, not as a central reference but as a kind of ambient presence. Could you talk about how your interest in Fisher came into play, and how that eventually shaped the atmosphere or development of Suburban Hauntology?

Arash: I don’t see myself as someone who studies theory beforehand or builds my work around concepts. My process begins elsewhere with something I call visual deduction: a stage where I separate or remove a mass of things as far as seems necessary and spend a long time thinking about their connections. Or more precisely, about the undiscovered parts of their connections, those that are often interpreted as empty spaces.

One example is the Capital series, which I developed between 2008 and 2015. It was a kind of biopsy of Tehran as a post-war city. The project began with photography, but after a while I reached a point where I felt the need to strip away everything color, texture, any excess. Through a digital process, I transformed the urban space into something that looked like a graphic or environmental design. But these images were still photographs at the level of the pixel. What you see might look like a drawing, but it’s actually a photo that’s been emptied out. A large part of the original image is simply no longer there.

This reduction led to a shift in how the city was seen, or rather, how it could be read. Once I removed the colorful chaos, the pollution, the crowds, what was left was something flat and uniform. But that flatness was not accidental. It echoed what the post-revolutionary state had tried to do through its own urban design, a deliberate attempt to build a unified, state-managed city. A city without contradictions. And in my work, by reducing the image, the viewer becomes aware that what they’re looking at isn’t just form, it’s text. A mass of plain calligraphy, often large-scale, sometimes accompanied by murals, written across the walls of the city. Slogans, ideological statements, religious messages, and state propaganda. What interested me was how this visual noise, something people usually stop seeing could be made visible again just by removing what distracts from it. The simplification wasn’t aesthetic, it was a way of forcing a different kind of engagement, a form of reading.

At the same time, another transformation was happening. For a period after the revolution and during the war, commercial advertising had been almost entirely removed from Tehran’s public space. But in the post-war years, the so-called “Reconstruction Era”, it began to return. Slowly, almost quietly, private advertising started reappearing on the same walls that carried state slogans. The result was a kind of blending, or coexistence. Commercial messages began to sit right next to ideological ones. And that’s where something fascinating happened: the very regime that once erased advertising was now allowing, or even creating, a new kind of textual city, where religious slogans, moral guidance, and capitalist ads all shared the same space. And this produced a tension. You started to see how these overlapping texts contradicted each other. The ideological voice of the early revolution was still present, but now surrounded by the logic of consumerism, private capital, and the aesthetics of marketing. The city began to betray the contradictions of the system that built it. Commercial advertising didn’t just return, it destabilized the totalitarian visual order of the city.

This contradiction goes even deeper. Just as the state had once designed a uniform visual and ideological landscape, it had also intended for these slogans and texts to be read by the public. Reading them was part of the ideological program. But when commercial texts re-entered the same public space, authorized by the same regime, they complicated this original order. The result was that ideological and commercial language began to overlap, and instead of reinforcing each other, they exposed the underlying cracks. They created a fragmented, unstable image of the city one that contradicted the unity the regime tried to build. This tension became visible through the very act of visual reduction. This is also why I chose to bring up the Capital series here. It’s not just about Tehran or about the past. It’s about what happens when you reduce an image. When you cut away texture and aesthetic detail, you reveal something else something that’s usually hidden. In this case, it was language. It was power. It was contradiction. That process, what I call visual deduction, is still part of how I work today. It’s not a method I invented, but it’s something I’ve internalized, a way of seeing that starts not from theory, but from the act of subtraction.

I see the void as the very element that shapes form and content-related relations. The connections between these spaces sometimes become so complex and layered that reading them becomes practically impossible. At this point, either you stop and move on to the next project, or, like me, you continue from the stage of creation to the point of collapse. This is where certain theoretical frameworks can help introduce you to yourself or clarify the structure of your work. So, your term “reverse approach” accurately applies to my work. You have subtly pointed out the relationship between Deleuze’s concept of the time-image and my work. In my practice, meaning does not arise from a clear linear narrative or logic, but rather emerges gradually or remains entirely suspended. I often think of the artist as a figure caught in a mental landscape, circling around unresolved questions rather than advancing. This is not a sign of failure or inertia; it is a space where intuition, memory, and contradiction build the form itself. That suspension, between thinking and doing, is where the work begins for me. I’m not trying to clarify. I’m trying to stay with the complexity and let it fragment and reassemble in unexpected ways.

I discovered Mark Fisher by chance through some of his ideas online, particularly discussions about his K-Punk blog. What struck me immediately was how his writings described a kind of collective cultural anxiety I had already been sensing but couldn’t quite articulate myself. At that point, I wasn’t reading him as a “reference” in the usual sense, but more like someone whose tone and preoccupations echoed something I was already trying to produce visually. Later, I read Ghosts of My Life, and that book stayed with me in a strange, ambient way, not as a central framework, but more like background radiation. Fisher’s discussions of lost futures, cultural stagnation, and temporal disjunction particularly his idea that we’re haunted by the future we were promised but never received helped shape the atmosphere of Suburban Hauntology.

So even though Jean Renaudie’s architecture was my primary material, Fisher helped me understand why those spaces felt so ghostly. The repetition of styles, the unfinished utopias, the sense that time had somehow stalled all of that is very present in my work. I wouldn’t call him a major influence in a structural way, but his thought definitely seeped into the tone and conceptual undercurrent of the series. In this moment of mounting instability, Fisher’s insight comes back with brutal clarity: “To be in the twenty-first century is nothing more than to have twentieth century culture on high-definition screens.” We’re not looking forward anymore. We’re watching the same cycles repeat, sharper, clearer, and more unbearable than before.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the word “sharper,” or high resolution. The idea of resolution, of surface clarity, connects directly to what I was doing in my Suburban Landscapes series. I worked on those drawings with extreme precision, sometimes pixel by pixel, without using vector software, only raster formats. Then I printed them at large scale, where what you really saw was a surface. A digital surface enlarged beyond its natural resolution. These were images reduced to their own sharpness, what I now call the system of alienation.

Arash Hanaei, Hashtag Flagged, Suburban Hauntology,Les Rencontres d’Arles, BMW Art Makers, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

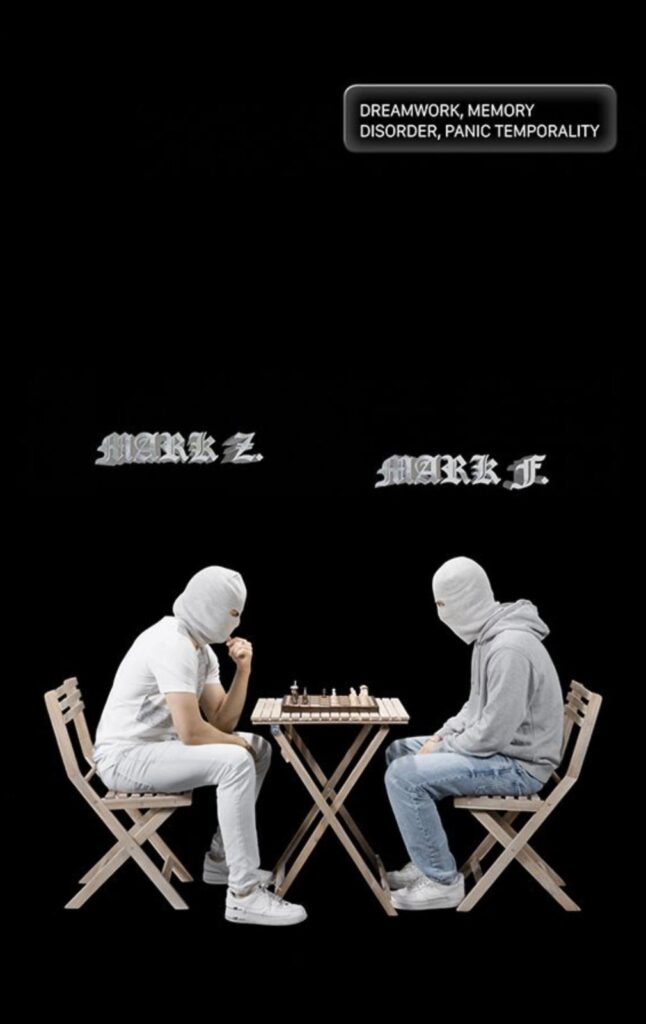

Arash Hanaei, Mark Z. vs. Mark F., Life Size Video-Installation, Suburban Hauntology, Les Rencontres d’Arles, BMW Art Makers, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Mahsan: More broadly, the way you describe the artist isn’t far from any human who chooses to live with unresolved questions, someone committed to staying with uncertainty rather than seeking fixed truths. It’s about accepting the subjectivity of thought, recognizing that even our attempts to be objective are shaped by our own perception and limitations. This includes the limits of language, which can never fully capture experience, and perhaps even the limits of perception itself. As an artist, you give form to fragmented thoughts without concealing your sense of being lost, where embracing uncertainty, ambiguity, and limitation becomes a kind of intellectual and creative courage.

For me, there’s a certain inner rigor that reveals itself through praxis—not as a message to be decoded, but as a form of truth that emerges from the process itself. It’s not about resolution or clarity, but about staying with the act of making, allowing the work to unfold meaning through persistence rather than explanation. Sometimes, essence might be found in failure, collapse, or even silence: states that resist narrative but nonetheless speak.

If in the Capital series you reduced the image to reveal what had been obscured, such as language, contradiction, or ideology, in another body of work you moved in the opposite direction. You began from absence and built a visual field around it. You have worked on three narratives that begin without any images, stories that exist only in language, memory, or trace, and you attempted to reconstruct them through visual means. This feels like another mode of radical imagination: shaping visual realities from what is missing or erased. What draws you to stories that begin without images, only memory, voice, or language, and how do you work through the tension between absence and invention?

Arash: This whole sequence began with a single story: the death of a photojournalist in a war zone. When I heard he had been killed, my first thought was that if the photographer is gone, then so is the image. That absence became the starting point. I printed the account of his death on photographic paper. No picture, just the story. The lack of an image became the image. Then came the second. One of the most tragic stories I have ever heard. A former student of mine contacted me during a dangerous sea journey to Australia, traveling with other asylum seekers on a small boat. His voice carried something strange deeply emotional, as if he were already halfway between life and death. He was not sure he would survive. After that call, there was only silence. Then, finally, a message. He had made it. He told me everything, detail by detail. There were no photos, no footage. Just his words. The only image he sent was of the group smiling on the boat. It looked like a vacation. But the horror behind it was completely hidden. I tried to work with it, even made a video, but nothing felt honest enough. The story did not need to be shaped. It was already complete.

Inspired by these practices, I created a video installation titled Copies All the More Blurred, which, alongside Foggy Memo, marks the beginning of this final sequence. Drawing on Jean Baudrillard’s theory of simulacrum and simulation, the work explores how our encounters in the post-internet world are increasingly shaped by mediated experiences that obscure truth and reality. The installation features a series of empty dog cages, referencing Oleg Kulik and Mila Bredihina’s Pavlov’s Dog (Manifesta 1, 1996), accompanied by barking sounds. Without a live performer, the cages evoke a spectral repetition of the original, building a metaphor of recursive replication: a copy of a copy of a copy. The placement of the video at the far end of the installation enhances this sense of distance, inviting the viewer to traverse layers of distortion. The video itself revisits the tragic 2015 Paris attacks, tracing the event through messages exchanged by residents. As the attack unfolds, local communications reflect growing anxiety and intimacy, while distant reactions, filtered through media and social networks, become increasingly abstract, reactive, or speculative. The contrast underscores the widening gap between firsthand experience and its reproduced versions, revealing how even trauma is shaped and diluted by systems of circulation and simulation.

Now I am working on another story: a leaked audio recording of a pilot who witnessed the missile strike on Flight PS752. He saw the explosion’s flash and tried to contact the control tower. But the blast had already happened. The recording shows they knew in that very moment. But the truth was buried. But now, in my current work, that has shifted completely. I’ve started returning to photography. I’m building textures and patterns again this time not to simplify the image, but to interrupt it, break it down, or even collapse it. I’m working with family photographs, Straight images, fragments from old albums. I layer them, superimpose them, distort them. Sometimes I listen to electronic music while doing it or collaborate with musicians. I use that rhythm, that distortion, to literally collapse the image into something unstable. This is not about clean surfaces anymore. The compositions are less rigid, less geometric less “designed,” more fragmented and free.

This new series is called An Unsuccessful Landing. It’s built on memories I avoided for years. I never brought them into my work until now, not formally, not mentally. These are fragments I hid, and now I’m using them. If I look at my work as a sequence, I can say I’ve done three major periods: the Capital Series, the Suburban Landscapes, and now An Unsuccessful Landing. This last one is different. It’s not about a city or a political structure. It’s a mental landscape. That’s where I am now.

Mahsan: This shift in your work makes me wonder whether, in some sense, you’ve chosen art as a form of escape from reality, or perhaps as a way to build a different reality altogether. But have you ever felt the opposite urge: to find an escape within reality itself, a safe place that doesn’t rely on artistic distance? Especially considering how you’ve explored utopian ideas in art and architecture, visions that so often ended up collapsing into dystopian realities, and how even Mark Fisher, who tried to motivate people to find a way out of this hauntological culture, has in some ways become another romanticized, commodified trend. Do you ever feel caught in that tension between imagining an elsewhere and wanting to find shelter, that so-called Utopia, in the here and now?

Arash: As an artist working with post Internet strategies I can say we can no longer speak with certainty about escapism as we’ve lost the ability to even recognize the moment of departure. We can’t tell where the threshold begins or whether we’ve already crossed it. Because reality itself is a fractured and contradictory landscape, composed of complexity, rupture, overlapping timelines, spatial displacements, and mental states with no fixed location or duration.

What we call “reality” and what we imagine ourselves moving toward or away from are both in constant flux. Along the way, production and mental states become entangled, sometimes in a way that borders on madness, until you no longer know whether you are escaping or repeating living reality. If, like me, you believe that outcome-oriented thinking has no real place in the work, then this state can become the source of constant transformation in different realities.

Perhaps this disintegration, this madness, is exactly what artists need in the world of big data: something beyond the professional models and methods that have been reduced by art market logic aiming to professionalize artists. Along this path, reduction and erosion can reach a radical point where no trace of work remains. And if it comes to that, I have left the door open, even if it leads to collapse. This isn’t an easy decision; it carries its own complexity. But perhaps it’s still a path left to take. The refusal of complete form or the rejection of final solid thinking in my practice may ultimately transform into another form of romanticized gesture. This risk is always present. However, it doesn’t mean that these choices are mistakes. Rather, it is because the very structure of power and sometimes public taste has the ability to turn any form of escape into a trap.

In my latest sequence, An Unsuccessful Landing, I’m drawn to the ways in which utopian ideals intersect with early spaces of memory such as the architecture of family homes. This line of thought first emerged years ago while I was photographing one of the large, almost unreal complexes in the southern suburbs of Paris. The image of that futuristic landscape triggered a return to my childhood apartment in Tehran, a space defined by filtered light, patterned surfaces, and a sense of static time. I remember the repetitive sound of pages turning as my mother read, the stillness of the rooms, and the quiet texture of daily life. This moment, reduced to a fragment, became the conceptual entry point for the first chapter of my series titled Family Fails.

In this chapter, I ask whether something resembling utopia might have been projected onto the domestic spaces of early life at a time when one’s grasp of reality is still forming. As a child, the world appears structured but is not yet legible. One inhabits it without fully understanding its systems or contradictions. Adaptation occurs but without the capacity to critically engage with the complexity of what is being absorbed. The series reflects on how memory constructs perception and whether our idealized impressions of the past are less about truth and more about the absence of disillusionment. These reflections run parallel to larger questions about reality and imagination, suggesting that the architecture of memory is inseparable from the way we formulate ideas of utopia.

Arash Hanaei, Unsuccessful Landing, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

Arash Hanaei, Unsuccessful Landing, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.