Florence Bonnefous: “I think we’ll go smaller, a bit like free jazz, and leaving Art Basel last summer was part of that.”

Mahsan: How did Air de Paris start, and how would you describe what shaped its identity?

Florence: Air de Paris was co-founded by Édouard Merino and me. We met in Grenoble, when we were doing our master in artistic mediation at L’École du Magasin, in 1988, I think. And when we finished, we were wondering what to do next. We weren’t a couple, but we were very close in the way of thinking. We liked the same art; we acted in a similar way with curiosity and nonchalance. At that time, we didn’t really know what to do together, there weren’t so many examples of collectives. In the years that followed, it happened that we showed a lot of collectives and collaborations, probably because we ourselves were already collaborating, and we created Air de Paris at a moment when it wasn’t so common. So, we thought the only way to do it together was to open a gallery where we could be independent, where we didn’t have to answer to anyone, and we could do what we wanted.

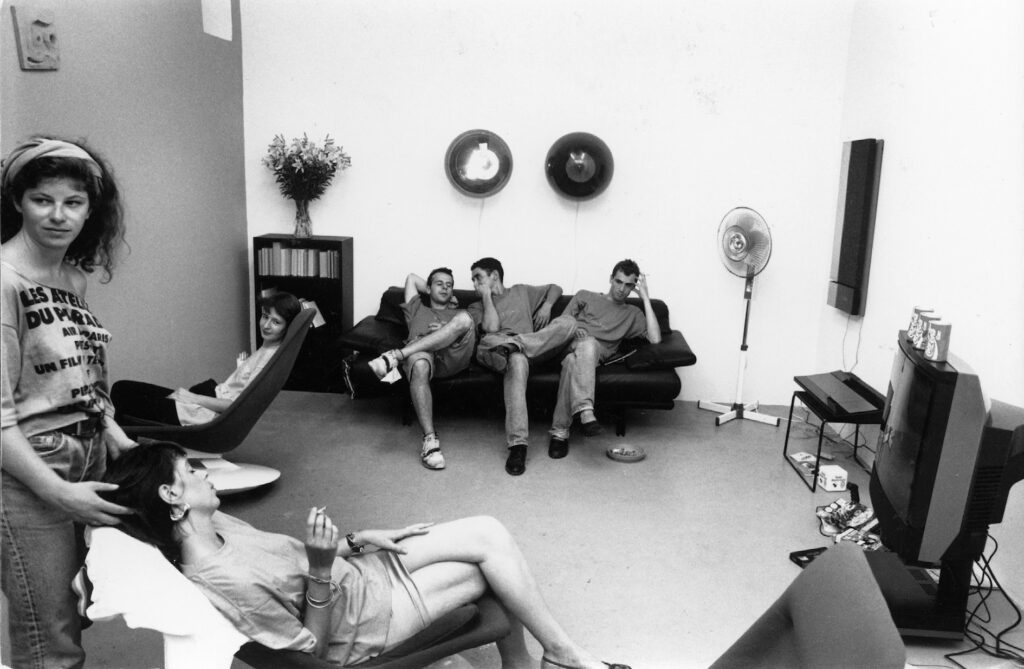

We started with an exhibition that was a bit unusual, called Les Ateliers du Paradise, a project by Pierre Joseph, Philippe Parreno, and Philippe Perrin, three artists we met in Grenoble when we were doing the training in 1989 and 1990. They moved to Nice with us. It also shows how impulsive it was. It was a group of people who were connected. Artists, us becoming gallerists, and other friends, a couple of young curators and art critics. And just like that, everyone came to Nice. It was very lively. Before that, we thought we would establish ourselves in Paris, and we found a space. But at the last minute, we didn’t sign the lease, because we thought that in Paris, we would be too much in the center of things, and probably lost, being with everyone. So, we decided we shouldn’t stay in Paris. We left for Nice.

The idea was to be next to the sea, to place the horizon in front of us. That was also facilitated by the fact that my partner is from Monaco. We could stay with his parents while looking for a place for me to live, and a space for the gallery to open. We had meetings by the sea, friend-ships facing the sea, the horizon, and a group of artists. A collective that changed the gallery into a place to live. We lived there more or less together, of course not sleeping much, but happily doing a lot of things. And then this was the start of the programming, with a lot of collaborations, and also works, or productions, coming from many different fields. And someone defined, one day, what we do, the way we intuitively brought things together, as “conceptual trash” or “conceptual outsider.” That’s how we started.

From left to right: Philippe Parreno, Ingrid Berthon Moine, Philippe Perrin, Edouard

Merino, Ingrid Luche, Florence Bonnefous, Pierre Joseph. Photo: Helmut Newton,

Merino Collection, Monaco, 1991. Courtesy of Air de Paris

Mahsan: When you did Les Ateliers du Paradise in 1990, “relational aesthetics” had not yet been coined as a term. At the time, what did you feel close to, like Fluxus or other references?

Florence: Relational aesthetics is something that was developed by Nicolas Bourriaud. He started writing his book Relational Aesthetics in 1995, and it was published in 1998. And he was someone who was often in Nice at the very beginning. Probably one could say that relational aesthetics is partly rooted in the experience of Les Ateliers du Paradise. But we had no idea of it, because we were doing it. When you do things, you don’t know what you’re doing. So, we didn’t know yet. But we did know that we felt very connected to Fluxus. French Fluxus was based in Villefranche-sur-Mer, which is quite close to Nice. That’s where Georges Brecht and Robert Filliou set up “La Cédille qui Sourit,” on rue de May, which later became the “Centre International de Création Permanente” and “The Eternal Network”. And it happens that Édouard’s parents were patrons of those guys. It was mostly Filliou and Brecht and their family, but it was also open to many artists who passed through this little studio and this little city by the Mediterranean sea. Including Dorothy Iannone, whose estate I am now the executrix of since she passed away in 2023. We met her by chance in 2006; and she used to visit the South of France a lot, and she was a very close friend of Filliou. So yes, everyone was deeply connected to Fluxus but not trying to do the same. More feeling connected.

One memory I have, which refers directly to “La Cédille qui Sourit,” is a small event we did with Philippe Perrin. As students, a lot of people would go to the beach at night, light bonfires, and drink in front of the sea. We went there for a kind of party with a porchetta and watermelon vodka. We attached our porchetta to a skateboard and carried it to the beach party. So it was like a procession, a line of people walking to the beach. In Nice it’s a beach with stones, not sand, a kind of clean beach, more like a city beach. You can go there to rest and then go to work. And we made that party, with this food, porchetta, into an event called La Porchetta qui Sourit, in reference to “La Cédille qui Sourit.” But otherwise, apart from that moment, we never really quoted Fluxus, even though we were close to some people who were still alive and who had been there, like Ben of course. There was also one artist Edouard and I liked very much, called Serge Oldenbourg, aka Serge III. He got famous in the 60s for a performance on the Promenade des Anglais, hitchhiking with a huge piano.

Mahsan: After Les Ateliers du Paradise, Georges Rey made the film Les enfants gâtés de l’art, a kind of making-of where everyone plays an exaggerated version of themselves. Why that title?

Florence: We didn’t choose the title. It was Georges Rey, the filmmaker. He was actually a teacher at the art school in Grenoble, where the three artists had studied. Georges Rey also ran a cinema in Lyon, and because Grenoble and Lyon are not so far, he was around. He was also an experimental filmmaker. By then he was already a bit well known for a film that was basically one fixed shot, a close-up on a big cow, in black and white. The cow is sitting in a field. Sometimes you see a bee flying, you see one ear moving, not much happens. And then, after a moment, people start to laugh, because you’re in a cinema and they’re showing you a cow. It’s a little absurd. And then the cow starts turning its head, and there is a kind of small action that happens between the public and the cow, the subject of the film. It was really funny. In the end, everybody was always laughing a lot, and it’s just about a cow. It’s a bit like Andy Warhol’s Sleep, but in the countryside, and it turns into a comedy. And Georges Rey is the one who came to make the film about the spoiled art brats.

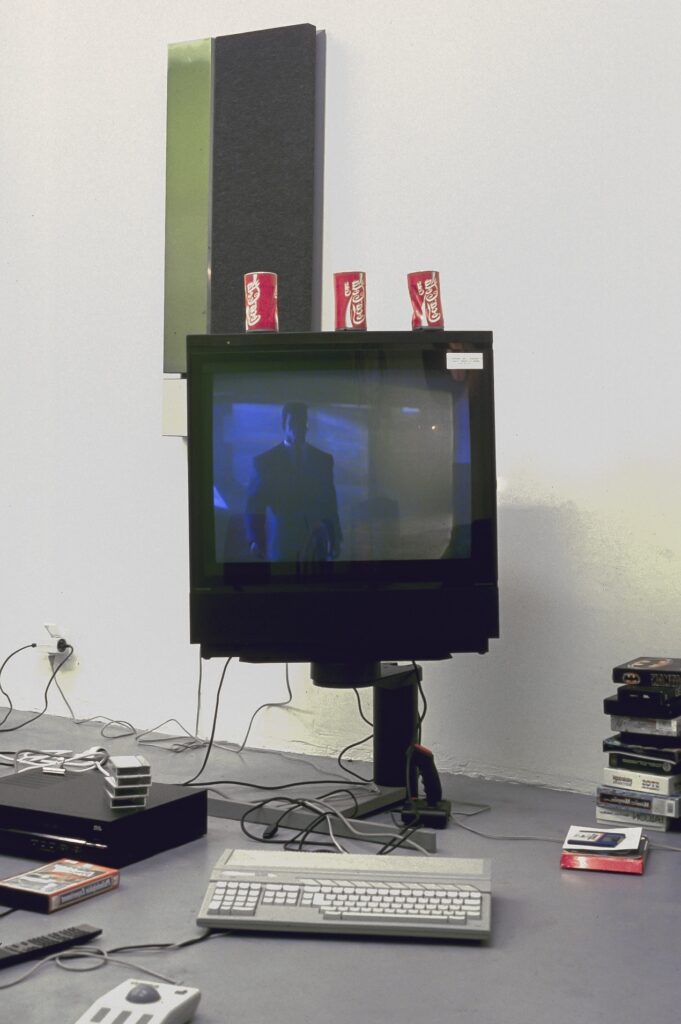

Les Ateliers du Paradise, Air de Paris, Nice, 1990. Photo: Jean-Marc Pharisien. Courtesy of Air de Paris

Les Ateliers du Paradise, Air de Paris, Nice, 1990. Photo: Jean-Marc Pharisien. Courtesy of Air de Paris

Les Ateliers du Paradise, Air de Paris, Nice, 1990.

Photos: François Fernandez. Courtesy of Air de Paris

Les Ateliers du Paradise, Air de Paris, Nice, 1990.

Photos: François Fernandez. Courtesy of Air de Paris

Mahsan: You have a very creative approach to curating. Where do you think that comes from?

Florence: I never really saw myself as a curator. When I do exhibitions, people may see them as curated. For instance, a recent exhibition I did with Liam Gillick, Ronald Jones, and Noah Barker was clearly built around a discussion, so yes, in that sense it was curated. But even then, I never signed it as “curated by” in my name. Basically, everything Edouard and I do ourselves stays under the gallery, unless we invite someone, and then we add the credit “curated by.” I’m a gallerist, and I like finding ways to make exhibitions. Selling art is the basic definition of a gallerist, and of course I have to do it. But my main pleasure is not really in selling, it’s in organizing exhibitions. Still, I need to sell, and everyone is happy if I sell. It’s a need. Artists need it, and everybody needs money to have a certain amount of liberty. We need a certain amount of money, and today it’s almost impossible to extract yourself from that system.

I don’t consider myself a curator or an artist, and Édouard doesn’t either. We think of ourselves as a playful duo, and almost every exhibition is, in a way, a portrait of us. It’s an expression, and a way of commenting on what art is, what politics is, and so on. And I collaborate with the artists a lot. I’m close to them, often very close. I have no problem suggesting that they try different things. There is this kind of interaction. Now that I’m getting older, I’m a bit of a mama for some of the younger ones. So, it’s more based on those friendly relationships than on calling yourself this or that.

Mahsan: You said you work a lot through collaboration with artists. With Domino, where each artist invited the next artist, how did that idea start?

Florence: Domino was obviously following the idea of a game, and rules. Putting rules in place for a game can also be a way, sometimes, to bring forward a structure that can be perverted, that can be disturbed. And the rules of a game, somehow, always offer the potential for surprises. Still, one can cheat … Also, in a physical way, the more you constrain something, the more likely there can be an explosion, and it goes out of the constraint. A bit like revolutions are, somehow, the result of a strict amount of pressure and a constrained structure. When soft liberalism is another way to keep people still, because they will integrate this as their own desires, which is not true. So that’s true with structures. This structure refers to Oulipo. Oulipo stands for “Ouvroir de littérature potentielle.” It is a literature movement that started in the 1960s, after the Nouveau Roman. The most well-known example is Georges Perec’s book La Disparition, which is written without any “e.” And it’s also this idea that the more difficult the challenge, the more chances you have to find something new and surprising.

There is also Le Château des Destins Croisés (The Castle of Crossed Destinies), another famous Oulipian book by Italo Calvino, written according to Oulipian structures. It is a kind of tarot game. When we did an exchange with the Chateau Shatto gallery in Los Angeles, we used the inverted title of The Castle of Crossed Destinies for an exhibition bringing together three artists, all born in 1934: Dorothy Iannone, Jef Geys, and Guy de Cointet. The Castle of Crossed Destinies meets The Destiny of the Crossed Castles—our galleries, our destinies, our choices.

Le Destin Des Châteaux Croisés, Air de Paris, Paris and Château Shatto, Los Angeles, 2018. Photo: Elon Schoenholz. Courtesy of Air de Paris

Mahsan: And what about No Ghost Just a Shell, by Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno? How did that project connect to Air de Paris for you?

Florence: This is a huge project that we followed, for many years. By then we were working very closely with Philippe, and Pierre Huyghe had no gallery in France, because his gallerist had just passed away. Also, somehow, we were the only gallery, the reference gallery for that project at the beginning. And we had many artists working and producing pieces for that project. But these were their rules. We were there to help produce, and we organized the launch. But we didn’t structure the project. It was really the artists’ project. And with some of the same artists, before that, there was a project called Vicinato. It started with a first film in 1995 with Carsten Höller, Philippe Parreno, and Rirkrit Tiravanija, produced by Claudio Guenzani and shot on the rooftop of a building in Milan. And then there was the second one, Vicinato 2, with the same artists plus Liam Gillick, Douglas Gordon, and Pierre Huyghe. And this was a film that we shot and completely produced in Monte Carlo, in a hotel on the high corniche, Hotel V, with a huge blue V neon that could be seen from afar, from land or sea. I think these collaborations, Les Ateliers du Paradise, or the following collaborations between Parreno and Pierre Joseph, like Snaking, all of that led to this gigantic project of Ann Lee about authorship. Beforehand, Parreno and Joseph had invented a sport called Snaking. A specific outfit was created, a hybrid between a diver and a mermaid, and we crawled all the way to the sea. Vicinato 1, Vicinato 2, Snaking… I think all these experiences led to Ann Lee.

Mahsan: When you decide to work with an artist, what guides that choice for you? Do you have certain criteria? And since you’ve said that selling is necessary, but it’s not the main pleasure, how do you keep the balance between supporting more difficult work and keeping the gallery going?

Florence: I think we have managed, by collaborating, to bring many artists to the front of the scene, and then we follow them to a certain point. Many of them we still work with. We stopped when we could not afford anymore, for instance, at one point Parreno went into huge projects like machine operas, the production costs were over a million euros, and we could not follow anymore. But we have been able to help artists reach success, and we know that we can, at some point in the future, help make money from a work that is just beginning and seems unsellable to everyone. You always find a balance. Since we have always known how to work with new artists, and we kept adding new ones, at one point they were maybe too many. But the sales of the older artists could pay for putting on the exhibitions of the younger artists. So, after the first few years that were a bit difficult, somehow, we could make an omelet with our own eggs.

Mahsan: It’s very important for you to stay faithful to artists over the long term. Even if some relationships can’t fulfill every expectation forever, with most artists the bond becomes close, even friendly. And you never stop working with an artist just because the work is not selling, even though the present moment feels difficult, financially and physically. That makes me wonder why not many people try to resist this market-driven homogenization in the art scene. Realistically, as you say, it’s almost impossible to be outside the market, but why is it so rare to at least try to act differently?

Florence: I would be happy if there were more people like that. I think it would change our lives and the art world a lot. Yes, I am faithful to people and to ideas. There’s a film by John Carpenter, one of his early films, called They Live. It’s a kind of science-fiction film, not really horror. It’s a dystopian movie. In it, people living in the city are required to wear glasses. It’s like a government rule. You put the glasses on, and you never take them off. They walk through the city and they see messages everywhere like, “Life is so beautiful,” “Isn’t it a good day?”, “Aren’t you happy?” And then one day someone takes the glasses off, and in fact all the messages are, “Obey,” “Never rebel.” So, we learn that this is the neoliberal structure. We learn to become what they want us to be, and we also learn to quit.

Mahsan: You’ve always been close to radical politics and radical styles, and your recent open letter to Art Basel, when you withdrew from the fair, was another strong gesture. How do you see today’s art world? And what place do you think rebellion still has in it?

Florence: Yes, I am openly pro-Palestinian, ultra-left-wing, and close to anarchist and situationist teachings. This is, of course, a personal position that does not imply that my close colleagues think the same way. I realize I sound a bit ridiculous when I say that; I also practice yoga and I Ching a lot, and I follow Buddhist principles to understand the world.

I don’t see much rebellion, and now I’m also a bit stuck with the art market. Maybe because I’ve been a gallerist for so many years now, more than 35 years, and we see less and less rebellion in the art world. And of course, I don’t like the art world as it is now. It’s okay, because I’m not going to do this for ten more years. So, I’m starting to think about slowing down the front-line activity. We already started to do fewer fairs. When I want my dose of rebellion, I go to demonstrations, anti-fascist demonstrations. And then I get something, I feel some reward. I don’t see such things, or very little, in the art world. As I said, you can’t really be outside the system, but you can step back. And for me that means slowing down. We did a big show in Monte Carlo in an empty flat last summer. We want to follow some projects there, temporary projects. We are currently thinking of a project that would pair films and artworks, one film, one artwork. One evening, one discussion. So, we are developing some projects in Monte Carlo.

I also just bought a house in the countryside, on the Plateau de Millevaches, with my husband Bruno Serralongue, who is an artist. It’s actually the first house I ever bought, my first property. It was a bit strange at the beginning, but I’m slowly getting used to it. We called the house “La Realidad,” which is the name of a Zapatista village (caracol) in Chiapas, Mexico, where they experiment with new ways of collective living. That was the village of Subcomandante Marcos in the 1990s. I went there in 1996 (I met my husband there) and it’s one of the rebellions I felt close to the most in recent years, as something alive, not something of the past. You know, Kropotkin is dead, Bakunin is dead, those anarchist figures, they aren’t there anymore. But in Chiapas, in the jungle, you have people who try to structure society on a smaller scale, differently, in the countryside.

I think we’ll go smaller, a bit like free jazz, you know. And leaving Basel last summer was kind of like that. And I’ve been very happy with some of the responses I got. I felt that maybe I spoke for many people who think like that but don’t dare to say it out loud. So maybe there is no obligation to stay with these bigger places, the bigger rooms, more fairs, a lot of travel. Maybe it will eventually lead to what we call “décroissance.” It’s maybe the direction we’re going now. Maybe like dimming the light, or the sound.

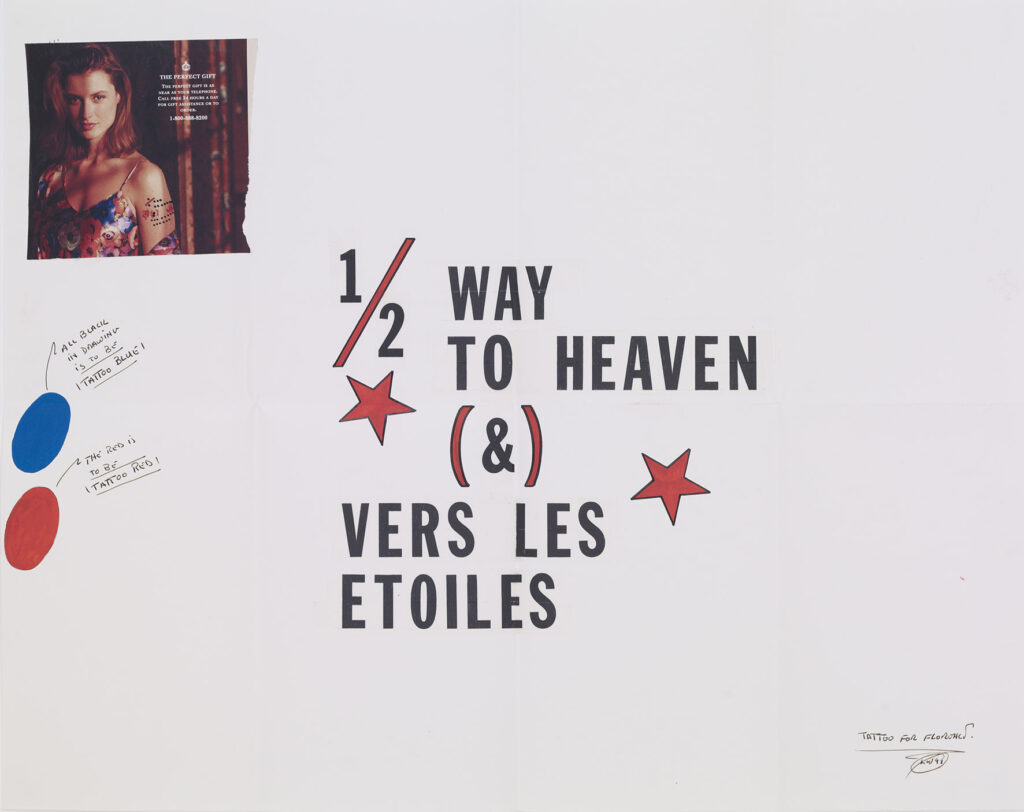

Florence Bonnefous and Gilles Dusein at the swimming pool of Hôtel Lapérouse, Nice,1991. Florence wears a tattoo by Lawrence Weiner (Tattoo n°1 (1/2 way to heaven), 1991), and Gilles has just been tattooed with Philippe Perrin’s Beretta Starkiller. Photo: Jean-Marc Pharisien

Lawrence Weiner, Tattoo n°1 (1/2 way to heaven), 1991, collage and ink on tracing paper, 48 × 60 cm, signed and dated on the front. Photo: Marc Domage